Pioneers of Positive Psychology (Part2)

Several humanistic psychologists, most notably Abraham Maslow, Carl Rogers, and Erich Fromm, developed theories and practices related to human happiness and flourishing. Nonetheless, recent empirical support has emerged for those approaches, and scholars have advanced their ideas. Positive Psychology owes its success to the efforts and contributions of numerous pioneers (in addition to Martin Seligman), such as Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, Christopher Peterson, Sonja Lyubomirsky, Barbara Fredrickson, Ed Diener, Paul Wong, and many more scientists who have worked hard to bring people happiness and well-being.

Mihaly Czikszentmihalyi

Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi (September 1934 – October 2021) was a Hungarian American psychologist who discovered and named the psychological concept of flow, a highly focused mental state conducive to productivity. He was a leading positive psychology researcher and has worked extensively on happiness, creativity and motivation. Csikszentmihalyi studied what makes people happy and pioneered the "experience sampling method" to discover what he called "the psychology of optimal experience," precisely speaking, the experience of flow.

Flow: The Science of Peak Performance

Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi described flow (1970s) as “being completely involved in an activity for its own sake. The ego falls away, and time flies. Every action, movement, and thought inevitably follows from the previous one, like playing music. Your whole being is involved, and you’re using your skills to the utmost.” Achieving flow can be a great way to make our activities more engaging and enjoyable. People often perform better and improve their skills when in a flow state.

In the state of flow, you feel completely at one with what you’re doing; you are in total control, so-called “in the zone,” and in complete focus. Flow (or being in the zone) happens in those moments of exquisite attention and total absorption when you get so focused on the task at hand that everything else disappears, and all aspects of performance, mental and physical, go through the roof.

Csikszentmihalyi identified three causes for flow: immediate feedback, the potential to succeed and feeling engrossed in the experience. He described seven characteristic features of flow: 1) intense and focused concentration, 2) a merger of action and awareness, 3) clarity of goals (purpose and objectives), 4) loss of reflective self-consciousness, 5) a sense of agency or personal control, 6) distortion of temporal experience and 7) experiencing the activity as intrinsically rewarding (autotelic experience). Other researchers have validated and extended these ideas. Moreover, they confirmed that Csikszentmihalyi was correct in his choice of words. “Flow” is indeed the proper term for the experience.

The state of flow emerges from a radical alteration in brain functioning. In flow, as attention heightens, the slower, energy-expensive extrinsic system (conscious processing) is replaced by the far faster, more efficient intrinsic system (subconscious processing). The technical term for this exchange is “transient hypofrontality,” with “hypo” (meaning slow) being the opposite of “hyper” (fast) and “frontal”, referring to the prefrontal cortex, the part of our brain that houses our higher cognitive functions. This transition is one of the main reasons flow feels flowy because any brain structure that would hamper rapid-fire decision-making is shut off.

Self-monitoring (self-consciousness) is the voice of doubt, the defeatist nagging of our inner critic. Since “flow” is a fluid state, where problem-solving is nearly automatic, second-guessing can only slow that process. When the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex quietens, those doubts are cut off at the source. The result is liberation. We act without hesitation, creativity flows more freely, risk-taking becomes less frightening, and the whole combination lets us flow. Changes in brainwave functioning promote this process. In flow, we shift from the fast-moving beta wave of waking consciousness to the far slower borderline between alpha and theta.

Finally, there’s the neurochemistry of flow. A team of neuroscientists at Bonn University in Germany discovered that endorphins are part of flow’s hormonal cocktail, including norepinephrine, dopamine, anandamide and serotonin. All five are pleasure-inducing, performance-enhancing neurochemicals that boost muscle reaction times, attention, pattern recognition and lateral thinking. This neurobiology tells us that we have probably cracked the optimal performance code (which is a big deal).

The Flow State

According to Csikszentmihalyi, ten factors accompany the experience of flow. While many of these components may be present, it is not necessary to experience all of them for flow to occur:

Clear goals that, while challenging, are still attainable.

The intense concentration and focused attention.

The activity is intrinsically rewarding.

Feelings of serenity, losing feelings of self-consciousness.

Timelessness: a distorted sense of time; feeling so focused on the present that you lose track of time passing.

Immediate feedback.

Knowing the task is doable, a balance between skill level and the existing challenge.

Feelings of having personal control over the situation and the outcome.

Lack of awareness of physical needs.

Complete focus on the activity itself.

If you are trying to achieve flow, it can help if a) you have a specific goal and plan of action, b) it is an activity that you enjoy or are passionate about, c) there is an element of challenge, and d) you can stretch your current skill level (at least slightly).

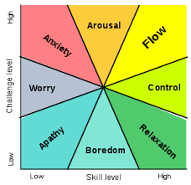

Csikszentmihalyi explained that "flow happens when a person’s skills are fully involved in overcoming a challenge that is just about manageable. So, it acts as a magnet for learning new skills and increasing challenges.” He added, “If challenges are too low, one gets back to flow by increasing them. If challenges are too great, one can return to the flow state by learning new skills."

References and Further Reading

Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly. (1990). Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience.

Nakamura, J., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2009). Flow theory and research. Handbook of positive psychology, 195-206.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). The contribution of flow to positive psychology.

Seligman, M. E., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2014). Positive psychology: An introduction. In Flow and the Foundations of Positive Psychology (pp. 279-298). Springer, Dordrecht.

Nakamura, J., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2014). The concept of flow. In Flow and the Foundations of Positive Psychology (pp. 239-263). Springer, Dordrecht.

Cheruvu, Ria. (2018). The Neuroscience of Flow. 10.13140/RG.2.2.12520.57608.

Christopher Peterson

Christopher Peterson (1950- 2012) was an American psychologist, the science director of the VIA Institute on Character and co-author (with Martin Seligman) of Character Strengths and Virtues (for the classification of character strengths). He was noted for his work on optimism, health, and well-being and is one of the founders of positive psychology. Dr Peterson won the 2010 Golden Apple Award, the most prestigious teaching award at Michigan University.

Peterson produced two remarkable books that helped to establish the positive psychology movement. These are “A Primer in Positive Psychology” and “Character Virtues and Strengths” (with Martin Seligman). He wrote an ongoing blog for Psychology Today called The Good Life: Positive Psychology and what makes life worth living. When Peterson was asked for a concise definition of “positive psychology”, he said: “Other people matter, period.”

Sonja Lyubomirsky

Sonja Lyubomirsky (distinguished professor and vice-chair, University of California, Riverside) devoted most of her research career to studying human happiness. Her research addressed three critical questions: 1) What makes people happy? 2) Is happiness a good thing? 3) How can people learn to lead happier and more flourishing lives?

Drawing on her ground-breaking research with thousands of people, Sonja Lyubomirsky has pioneered a detailed yet easy-to-follow plan to increase happiness in our day-to-day lives. Her book The How of Happiness offers a comprehensive guide to understanding what happiness is and isn’t, and what brings us closer to the happy life we picture for ourselves.

In her book, The Myths of Happiness, Dr Lyubomirsky draws on the latest scientific research to show that believing in happiness myths can have toxic consequences. Not only do our false expectations turn into a full-blown crisis, but they may also steer us to make poor decisions and impair our mental health.

The Sustainable Happiness Model

The Sustainable Happiness Model (SHM; Lyubomirsky, Sheldon, & Schkade, 2005) provides a theoretical framework for experimental interventions aimed at increasing and maintaining happiness. According to this model, three factors contribute to an individual’s long-lasting happiness: a) the inherent set point, b) life circumstances, and c) intentional activities or effortful acts that are naturally variable and episodic. Such activities, including acts of kindness, expressing gratitude or optimism, and savouring joyful life events, represent the most promising route to sustaining enhanced happiness.

Future researchers must learn which practices make people happier and how and why they do so. Despite several barriers to greater well-being, the model suggests that less happy people can successfully strive to be happier by learning various effortful strategies and practising them with determination and commitment.

The Happiness Pie Chart

The happiness pie chart was initially proposed in a 2005 paper by researchers Sonja Lyubomirsky, Kennon Sheldon, and David Schkade. The happiness pie chart depicts what contributes to our well-being. Unfortunately for some of us, the chart suggests, the genes we inherited from our parents significantly affect how fulfilled we feel. But it also contains good news: by engaging in healthy mental and physical habits, we can still control our happiness.

This pie chart has received a lot of (valid) criticism, and the authors of the chart agree with much of it. They explained that subsequent research had supported the most crucial premise of the Sustainable Happiness Model (SHM), which gave rise to the pie chart. In other words, individuals can boost and maintain their well-being through intentional behaviours. However, such effects may be weaker than we initially believed. They describe three existing SHM-derived models: the Eudaimonic Activity Model, the Hedonic Adaptation Prevention model, and the Positive Activity Model. Research testing these models has further supported the premise that how people choose to live matters to their well-being.

Barbara Fredrickson

Barbara Fredrickson is a leading scholar in social psychology, affective science (the study of emotion) and positive psychology. Fredrickson’s work on studying positive emotions led to the development of Broaden and Build Theory. In 2013, Fredrickson released the book Love 2.0, which guides how to increase opportunities to receive and provide moments of love.

The work of Fredrickson and her colleagues has had a significant impact on the science of happiness. Their study of positive emotions, mainly “the big ten emotions” (i.e., love, joy, gratitude, serenity, interest, hope, pride, amusement, inspiration, and awe), has led to many happiness habits.

Building and maintaining strong relationships is directly linked to the need to care about friends and family and cultivate positive emotions in mutual experiences with them. The link between “caring” and positive emotions emerges when we care for others, creating opportunities to develop and experience (micro instances of) love. This fact is supported by independent research suggesting that volunteering often generates as much, if not more, positive emotion in the volunteer as in those receiving support.

Perhaps most closely connected would be Fredrickson’s study of gratitude and why it is an integral component of a positive mindset and happiness habit; “Gratitude opens your heart and carries the urge to give back, to do something good in return, either for the person who helped you or for someone else.” (Fredrickson, 2009).

Broaden and Build Theory of Positive Emotions

Fredrickson’s work on positive emotions, such as love, began in 1998 and led to a theory called the Broaden and Build Theory. The substance of this theory lies in the notion that positive emotions play an essential role in our survival.

Positive emotions like love, joy, and gratitude promote new and creative actions, ideas and social bonds. When people experience positive emotions, their minds broaden, opening to new possibilities and ideas. At the same time, positive emotions help people build their well-being resources, which consist of physical, intellectual, and social resources (Fredrickson 2009).

The building part of this theory is tied into the findings that these resources are durable and can be drawn upon later in different emotional states to maintain well-being. The theory also suggests that negative emotions serve the opposite function of positive ones. When threatened with negative emotions like anxiety, fear, frustration or anger, the mind constricts and focuses on the imposing threat (real or imagined), thus limiting one’s ability to be open to new ideas and build resources and relationships. Fredrickson draws on the imagery of the water lily to beautifully illustrate her theory: “Just as water lilies retract when sunlight fades, so do our minds when positivity fades” (Fredrickson 2009).

Barbara Fredrickson uses the term “positivity” to describe the experience of one or several positive emotions. Although each type of positivity feels unique and arises for different reasons, they all adhere to the same basic facts. The following are the facts worth knowing about positive emotions:

They don’t last long. Good feelings come and go.

They change how our mind works.

They transform our future. Although fleeting, their effect accumulates, helping us build physical, mental, and social resources over time. In other words, they can create upward spirals of positivity and health in our lives.

They can stop the downward spiral of negativity. Positivity can undo the harmful effects of stress, anxiety and general negativity (see Losada’s Ratio).

We can increase our positivity.

Fredrickson’s research has shown that positivity doesn’t simply reflect success and health. It can also produce success and health. It means that we can find traces of their impact even after our positive emotions fade. In other words, our positivity has lasting consequences in our lives. Positivity can be the difference between flourishing and languishing.

The Notorious Losada Ratio

In her 2009 book, Positivity, Fredrickson defines positivity and explains how it can transform people’s lives. At the time, her research showed a 3 to 1 positivity ratio as a unique “tipping point” between flourishing and languishing, an ideal suggestion for high-functioning teams, relationships and marriages. This ratio was known as the “critical positivity ratio,” sometimes called Losada’s Ratio, as it was calculated in collaboration with Marcial Losada (a Chilean psychologist).

Fredrickson explained that the ratio of positive to negative emotions (approximately 3 to 1) leads people to achieve optimal levels of well-being and resilience. This idea was a ground-breaking discovery in sparking discussions about how a positive state of mind can enhance relationships, improve health, relieve depression, and broaden the mind.

A 2013 study by Nicholas Brown, Alan Sokal, and Harris Friedman challenged the validity of Losada’s Ratio. Their concerns stemmed from an empirical viewpoint. They did not find any problem with the idea that positive emotion is more likely to build resilience or that a higher positivity ratio is more beneficial than a lower one. They found an issue in assigning mathematical applications to pinpoint that specific ratio (Brown et al., 2013).

Fredrickson responded to the criticism by agreeing that more study is necessary to designate a precise mathematical value/ratio; however, she stood firm that her research has adequately proved that the benefit of a high positivity-to-negativity ratio is solid: “Science, at its best, self-corrects”. We may now witness such self-correction as mathematically precise statements about positivity ratios give way to heuristic statements such as “higher is better, within bounds.” (Fredrickson, 2013). The door is open for further scientific study, and more data will come with time.

Love 2.0

Barbara Fredrickson released her book Love 2.0 (2013), which serves as a guide to increasing opportunities to receive and offer moments of love. Fredrickson described love as an emotion that, like all other emotions, is momentary, not enduring, and can be experienced in micro-moments (micro-doses).

Through this lens, love is not just for soul mates and family ties. Love 2.0 defines love as an emotion that can be shared with family members and strangers several times a day. Fredrickson found that the song “What a Wonderful World”, made famous by Louis Armstrong in the 1960s, fit her theory: “I see friends shaking hands….sayin ‘how do you do?’ / they’re really saying...’ I love you’” (Fredrickson 2013).

Fredrickson (2013) described love as a momentary emergence of three tightly interwoven events: first, a sharing of one or more positive emotions between you and another; second, synchrony between your and the other person’s biochemistry and behaviours; and third, a reflected motive to invest in each other’s well-being that brings mutual care. Then, a moment of love is created when these criteria are met. When a person finds another with whom they can share several such moments, bonds form, loyalty develops, and enduring relationships are created.

The Vagus Nerve and Social Connectivity

The vagus nerve (X cranial nerve or 10th cranial nerve) runs from the brain through the face and thorax to the abdomen and is a central component of our parasympathetic nervous system. A healthy vagal tone signals your body to click into the "Tend-and-Befriend or Rest-and-Digest” mode and turns off the "Fight-or-Flight" mechanism driven by the sympathetic nervous system.

Frederickson and Kok (2016) assessed vagus nerve function in various individuals. They found that a higher vagal tone is associated with activation of the vagus nerve and a parasympathetic response, and is better at self-regulating emotions. They hypothesised that a higher vagal tone was directly related to people’s ability to experience more positive emotions and to increase positive social connections. Having more social links would, in turn, increase vagal tone, thereby improving physical health and creating a positive cycle and self-perpetuating "upward spiral".

Upward Spiral Theory

In 2018, Fredrickson and Joiner published a paper reflecting on their 2002 article, which provided empirical support for their upward spiral hypotheses. Their conjecture was based on the broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions, which states that experiences of momentary mild positive emotions broaden people’s awareness and, over time, build substantial personal resources that contribute to their overall emotional and physical well-being.

They highlighted empirical and theoretical advancements in the scientific understanding of upward spiral dynamics associated with positive emotions, focusing on the new upward spiral theory of lifestyle change (Positive Emotions Trigger Upward Spirals Toward Emotional Well-Being).

The primary contribution of Fredrickson and Joiner (2002) was to demonstrate that everyday positive emotions (however fleeting) can initiate a cascade of psychological processes that have an enduring impact on people’s subsequent emotional well-being. Beyond making people feel good in the present, positive emotions also appear to increase the odds (through dynamic broaden-and-build processes) that people will feel good in the future. A strength of this study was its prospective design over five weeks.

Research has shown that healthy behaviours experienced as pleasant are more likely to be maintained. The upward spiral theory unpacks this relation, emphasising automatic, often nonconscious motives and mental and social resources that make people more sensitive to subsequent positive experiences. To the extent that positive affects (emotions) are experienced during healthy behaviour, the upward spiral theory suggests that they create unconscious motives that grow stronger over time as they are increasingly supported by the resources (both biological and psychological) that positive affects build.

Downward Spiral of Negativity

It’s a fact that the patterns of negative thinking breed negative emotions (and vice versa), so much so that they can even spiral down into pathological states, such as depression, phobias or obsessive-compulsive disorders. The reciprocal dynamic between negative thoughts and emotions is why downward spirals are so slippery. Negative thoughts and emotions feed on each other and pull us down into their gloomy abyss of negative states.

A downward spiral is often described as a depressive state where the person experiencing the downward spiral is getting more and more depressed, perhaps due to unknown causes. It is called a spiral because it seems there is no way to stop it.

Ed Diener

Ed Diener is a professor of psychology at the University of Utah and the University of Virginia. His research focuses on theories and measurement of well-being, the influence of temperament and personality on well-being, the relationship between income and well-being, cultural impacts on well-being, and how employee well-being enhances organisational performance.

Dr Diener has co-edited three books on subjective well-being. 1) Well-Being: The Foundations of Hedonic Psychology, 2) Advances in Quality-of-Life Theory and Research, and 3) Culture and Subjective Well-Being.

He coedited the Handbook of Multimethod Measurement in Psychology and wrote a popular book on Happiness with his son, Robert Biswas-Diener, and co-author of Well-Being for Public Policy.

Ilona Boniwell

Professor Ilona Boniwell, mentored by Martin Seligman, founded and directed the first Master of Applied Positive Psychology (MAPP) at the University of East London. She currently leads the International Master of Applied Positive Psychology (I-MAPP) at the University of Anglia Ruskin (the United Kingdom and France), teaches Positive leadership at École CentraleSupélec, conducts research in collaboration with the École Head of Economics in Moscow and writes a monthly column for the magazine: Positive Psychology.

Dr Boniwell obtained her doctorate at the Open University in England in 2000 and has taught at Oxford Brookes University and City University. She has written or participated in writing nine books and numerous scientific articles. She is the founder and first president of the European Network of Positive Psychology (ENPP), and she has been a member of the Management Committee for many years.

Dr Boniwell became an active member of the French and Francophone Association of Positive Psychology in Paris. In 2012, she brought her expertise to the government of Bhutan to develop a policy based on the people's happiness at the UN's request. In addition to her academic work, she is passionate about the practical applications of Positive Psychology in companies, education and coaching.

As director of Positran (a consulting company specialising in the application of fundamental methods of psychology), she works with her team in commercial companies and educational institutions around the world (France, the United Kingdom, Iceland, the Netherlands, Portugal, China, Singapore, Japan, etc.) to effect a lasting positive transformation. She has also developed a complete Wellbeing and Positivity at Work kit for the Government of Dubai.

Kate Hefferon

Dr Hefferon is a chartered research psychologist and an honorary reader at the University of East London. She has dedicated her academic studies to understanding the role of the body in well-being across various populations, topics and interventions. Dr Hefferon’s PhD thesis was on the experience of post-traumatic growth among female breast cancer survivors and the role of the body and physical activity in the recovery and growth process.

Dr Hefferon became the Programme Leader of the world-renowned Master's in Applied Positive Psychology (MAPP) at the University of East London (UEL). She founded and led the posttraumatic growth research unit at UEL and continues her affiliation with the Master’s in Applied Positive Psychology and Coaching Psychology (MAPPCP) at UEL.

Dr Hefferon’s research interests mainly focus on post-traumatic growth and the body and physical activity within clinical populations. She also took up a post at the University of the Arts, London College of Fashion, to pursue her interest in connections between clothing practices, the body, and wellbeing.

Another area in which Dr Hefferon is passionate about is qualitative approaches within the psychological sciences. She is an expert in qualitative research with over a decade of experience in facilitating, training and supervising novice and advanced researchers across various qualitative approaches. She co-founded the Scottish Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis Group (SIPAG), was a former co-facilitator of the London Regional IPA group and co-founded London IPA training.

Dr Hefferon is a member of the British Psychological Society (Division of Teachers and Researchers in Psychology), a fellow of the Higher Education Academy (Advance HE) and the Royal Society of Arts, a senior associate member of the Royal Society of Medicine (RSM) and a founding member of the Advisory Board for the European Network of Positive Psychology.

Itai Ivtzan

Dr Itai Ivtzan is a positive psychologist, a senior lecturer and the program leader of MAPP (Master’s in Applied Positive Psychology) at the University of East London (UEL). He is also an honorary senior research associate at University College London (UCL). He has published many books, journal papers and book chapters. His main research areas are spirituality, mindfulness, meaning and self-actualisation.

For many years, Dr Ivtzan has run seminars, lectures, workshops and retreats in the UK and worldwide, in various educational institutions and private events while focusing on different psychological and spiritual topics such as positive psychology, psychological and spiritual growth, consciousness and meditation.

Dr Ivtzan is confident that meditation can positively transform individuals and even the whole world. Accordingly, he has invested much time in studying, writing about, and teaching meditation.

Dr Ivtzan is also a qualified psychotherapist offering Awareness Coaching (a couple of sessions) and Awareness Therapy (many sessions) to help his clients remove unconscious blocks and achieve their full potential.

He is the author/co-author of Awareness is Freedom: The Adventure of Psychology and Spirituality, Mindfulness in Positive Psychology: The Science of Meditation and Wellbeing, Second Wave Positive Psychology: Embracing the Dark Side of Life, and Applied Positive Psychology: Integrated Positive Practice.

Time Lomas

Dr Lomas is a lecturer in positive psychology at the University of East London, seeking to drive the field into new and uncharted territory. Before being a positive psychology scholar, he was a singer in a Ska Band (a music genre that originated in Jamaica in the late 1950s and was the precursor to rocksteady and reggae), a psychiatric nursing assistant, and an English teacher in China.

Dr Lomas’ research and scholarly activities have produced 70 peer-reviewed journal papers and eight books (to 2020). He has focused his academic contributions on three main areas: mindfulness, positive psychology theory and cross-cultural lexicography.

Dr Lomas played a significant role in developing MAPP (Master’s in Applied Positive Psychology) at the University of East London (UEL), including serving as an associate programme leader responsible for distance learning (2014-2015). He has published the following books (as the author or the co-author).

Lomas, T., & Huett, A. (2019). Happiness: Found in Translation. Tarcher: New York.

Lomas, T. (2018). Translating Happiness: Enriching our Experience and Understanding of Wellbeing through Untranslatable Words. Boston, MA: MIT Press.

Lomas, T. (2018). The Happiness Dictionary: Untranslatable Words from Around the World to Help us Lead a Richer Life. London: Piatkus.

Lomas, T. (2016). The Positive Power of Negative Emotions: How to harness your darker feelings to help you see a brighter dawn. London: Piatkus.

Ivtzan, I., Lomas, T., Hefferon, K., & Worth, P. (2015). Second Wave Positive Psychology: Embracing the Dark Side of Life. London: Routledge.

Lomas, T. (2014). Masculinity, Meditation, and Mental Health. London: Palgrave MacMillan.

Lomas, T., Hefferon, K., & Ivtzan, I. (2014). Applied Positive Psychology: Integrated Positive Practice. London: Sage.

Paul Wong

Dr Wong is the professor emeritus of Trent University (Ontario, Canada), a fellow of the American Psychological Association (APA) and the Canadian Psychological Association (CPA), President of the International Network on Personal Meaning (www.meaning.ca) and the Meaning-Centred Counselling Institute. He is the architect of Meaning-Centred Counselling and Therapy (MCCT), an integrative, existential, positive approach to counselling, coaching, and psychotherapy. Dr Wong is also the editor of the International Journal of Existential Positive Psychology.

Dr Wong’s story is one of transformation and triumph despite tragedy. He started his life as a melancholic child in China, who grew into an impoverished refugee in Hong Kong and later a sincere convert to Christianity and a mistreated minister in Toronto. Dr Wong is now an influential professor and psychologist on the world stage, having spoken in multiple cities across four continents.

What are his survival and success secrets in this harsh and turbulent world? Dr Wong’s answer may be surprisingly simple, yet complicated: the pursuit of meaning! “There is no other motivation more powerful and more transformative. All my life, day in and day out, sunshine or storm, paid or unpaid, healthy or sick and even now in my old age, I have struggled in my quest for meaning with little reward or recognition. What has sustained me is the deep conviction that I can bring meaning and thus happiness to the suffering masses.”

Paul Wong is one of the pioneers who extended the second wave of positive psychology (PP 2.0) to Existential Positive Psychology (EPP) by formally incorporating the dialectical principles of Chinese psychology, the bio-behavioural model of adaptation and cross-cultural positive psychology.